Natural Language Processing with NLTK

A natural language is a language used by people to communicate with each other (like French or English). Researchers might be interested in studying various elements of language:

- Syntax. Do people with autism use pronouns differently than people without autism?

- Sentiment. Can we predict manic episodes by parsing the sentiment (emotional valence) of a patient’s social media posts?

- Auditory elements. Can “flat affect” be detected computationally in recordings and be used to detect a need to re-evaluate depression meds?

- Discourse. Is conversational turn-taking in a clinical setting related to outcomes? Are physician interruptions affecting patient health?

- Semantics. What topics are included in physician notes? Are there keywords or key phrases that could be predictive of a patient’s later diagnosis with MS?

- Complexity. Do some patients with poor school performance actually use words and syntactic structure well beyond their grade level? Is this linked to sensory processing disorder?

- Length. How do subject self-descriptions vary in length, and how does this correlate to compliance to research participation requirements?

Natural language processing is a computational discipline that combines domain-level expertise (such as knowing linguistic terminology and methods) and computational foundations (like string manipulation). There are multiple ways to perform NLP, but in this article I am concentrating on the use of the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK). Follow along as we analyze a text.

First, you’ll need to install NLTK using pip or conda (or your preferred installation method). NLTK has a lot of supplementary resources that are only downloaded as they are needed, so the first time you run a program using NLTK, you’ll probably be prompted to issue the command nltk.download(). Go ahead and just download everything – it will take awhile but then you’ll have what you need moving forward.

Once you’ve installed NLTK, we can get started using it. In the code below, I go through a natural progression of doing some experimental work to look at and visualize data, then optimize it for analysis. You’ll see errors and missteps along the way. The goal is to show you how to move forward in small, doable steps!

You can follow along below, or download the complete code.

The Code

import nltkBelow is where you might get prompted to do the full NLTK download. If so, do it! In the cell below, we’re loading up US Presidential inaugural addresses.

from nltk.corpus import inauguralWhat inaugural files are within this corpus?

Just show the first 10. Note that I could also have typed inaugural.fileids()[1:10]

inaugural.fileids()[:10]['1789-Washington.txt',

'1793-Washington.txt',

'1797-Adams.txt',

'1801-Jefferson.txt',

'1805-Jefferson.txt',

'1809-Madison.txt',

'1813-Madison.txt',

'1817-Monroe.txt',

'1821-Monroe.txt',

'1825-Adams.txt']

Get some overall stats about the corpus (body of texts) as a whole.

How many total words?

- I’m going to use a method (something that acts on a specific type of object, such as the

wordsmethod on an NLTK corpus) to get a word list. - Then I’ll use a function (something that lives outside object definitions and gets passed data to work on, like

len()) to get the length.

all_words = inaugural.words()

len(all_words)145735

An aside here about methods and functions. If you’re anything like me, and you work in a number of languages, you’ll forget often whether something is a method or a function. Is it head(mydata) or mydata.head()? There’s not much to be done except practice, practice, practice. However, you can see the methods available on an object, which might help. Try, for example, dir(inaugural). See how at the end you can see the word words? That can be a good reminder if you can’t exactly remember what methods are available to you. What are the double underscores all about? Those are attributes.

dir(inaugural)['CorpusView',

'__class__',

'__delattr__',

'__dict__',

'__dir__',

'__doc__',

'__eq__',

'__format__',

'__ge__',

'__getattribute__',

'__gt__',

'__hash__',

'__init__',

'__init_subclass__',

'__le__',

'__lt__',

'__module__',

'__ne__',

'__new__',

'__reduce__',

'__reduce_ex__',

'__repr__',

'__setattr__',

'__sizeof__',

'__str__',

'__subclasshook__',

'__unicode__',

'__weakref__',

'_encoding',

'_fileids',

'_get_root',

'_para_block_reader',

'_read_para_block',

'_read_sent_block',

'_read_word_block',

'_root',

'_sent_tokenizer',

'_tagset',

'_unload',

'_word_tokenizer',

'abspath',

'abspaths',

'citation',

'encoding',

'ensure_loaded',

'fileids',

'license',

'open',

'paras',

'raw',

'readme',

'root',

'sents',

'unicode_repr',

'words']

OK, back to text analysis. How many unique words are in the corpus?

len(set(all_words))9754

What are the most common words used?

nltk.FreqDist(all_words).most_common(30)[('the', 9281),

('of', 6970),

(',', 6840),

('and', 4991),

('.', 4676),

('to', 4311),

('in', 2527),

('a', 2134),

('our', 1905),

('that', 1688),

('be', 1460),

('is', 1403),

('we', 1141),

('for', 1075),

('by', 1036),

('it', 1011),

('which', 1002),

('have', 994),

('not', 916),

('as', 888),

('with', 886),

('will', 846),

('I', 831),

('are', 774),

('all', 758),

('their', 719),

('this', 700),

('The', 619),

('has', 611),

('people', 559)]

We see that both the and The have appeared in our word list. We will want to be aware of case sensitivity moving forward!

Check out individual word context

from nltk.text import Text

Text(inaugural.words()).concordance("nation")Displaying 25 of 302 matches:

to the character of an independent nation seems to have been distinguished by

f Heaven can never be expected on a nation that disregards the eternal rules o

first , the representatives of this nation , then consisting of little more th

, situation , and relations of this nation and country than any which had ever

, prosperity , and happiness of the nation I have acquired an habitual attachm

an be no spectacle presented by any nation more pleasing , more noble , majest

party for its own ends , not of the nation for the national good . If that sol

tures and the people throughout the nation . On this subject it might become m

if a personal esteem for the French nation , formed in a residence of seven ye

f our fellow - citizens by whatever nation , and if success can not be obtaine

y , continue His blessing upon this nation and its Government and give it all

powers so justly inspire . A rising nation , spread over a wide and fruitful l

ing now decided by the voice of the nation , announced according to the rules

ars witness to the fact that a just nation is trusted on its word when recours

e union of opinion which gives to a nation the blessing of harmony and the ben

uil suffrage of a free and virtuous nation , would under any circumstances hav

d spirit and united councils of the nation will be safeguards to its honor and

iction that the war with a powerful nation , which forms so prominent a featur

out breaking down the spirit of the nation , destroying all confidence in itse

ed on the military resources of the nation . These resources are amply suffici

the war to an honorable issue . Our nation is in number more than half that of

ndividually have been happy and the nation prosperous . Under this Constitutio

rights , and is able to protect the nation against injustice from foreign powe

great agricultural interest of the nation prospers under its protection . Loc

ak our Union , and demolish us as a nation . Our distance from Europe and the

Hone in on specific texts

Corpora are made of component texts. Let’s extract the first ten and last ten texts and compare the older to the newer texts. How has the language of inaugural addresses changed?

early_list = inaugural.fileids()[:10]

early_list['1789-Washington.txt',

'1793-Washington.txt',

'1797-Adams.txt',

'1801-Jefferson.txt',

'1805-Jefferson.txt',

'1809-Madison.txt',

'1813-Madison.txt',

'1817-Monroe.txt',

'1821-Monroe.txt',

'1825-Adams.txt']

recent_list = inaugural.fileids()[-10:]

# Note, I could also have done

# inaugural.fileids()[len(inaugural.fileids())-10:len(inaugural.fileids())]

recent_list['1973-Nixon.txt',

'1977-Carter.txt',

'1981-Reagan.txt',

'1985-Reagan.txt',

'1989-Bush.txt',

'1993-Clinton.txt',

'1997-Clinton.txt',

'2001-Bush.txt',

'2005-Bush.txt',

'2009-Obama.txt']

Here let’s do our first loop. In Python, whitespace indentation is important! It does the same thing as curly braces in other languages. We’ll also do a “list comprehension”, where we create a list by iterating over something.

for text in early_list:

word_list = inaugural.words(text)

# Below is our "list comprehension":

word_list = [w.lower() for w in word_list] # handle the case sensitivity

unique_words = len(set(word_list))

# In Python you can concatenate text with plus signs. I turn the number of unique words

# into a string before concatenating it to the rest.

print ("For text " + text + ", the number of unique words is", str(unique_words))For text 1789-Washington.txt, the number of unique words is 604

For text 1793-Washington.txt, the number of unique words is 95

For text 1797-Adams.txt, the number of unique words is 803

For text 1801-Jefferson.txt, the number of unique words is 687

For text 1805-Jefferson.txt, the number of unique words is 783

For text 1809-Madison.txt, the number of unique words is 526

For text 1813-Madison.txt, the number of unique words is 524

For text 1817-Monroe.txt, the number of unique words is 987

For text 1821-Monroe.txt, the number of unique words is 1213

For text 1825-Adams.txt, the number of unique words is 972

for text in recent_list:

word_list = inaugural.words(text)

# Below is our "list comprehension":

word_list = [w.lower() for w in word_list] # handle the case sensitivity

unique_words = len(set(word_list))

# In Python you can concatenate text with plus signs. I turn the number of unique words

# into a string before concatenating it to the rest.

print ("For text " + text + ", the number of unique words is", str(unique_words))For text 1973-Nixon.txt, the number of unique words is 516

For text 1977-Carter.txt, the number of unique words is 504

For text 1981-Reagan.txt, the number of unique words is 855

For text 1985-Reagan.txt, the number of unique words is 876

For text 1989-Bush.txt, the number of unique words is 754

For text 1993-Clinton.txt, the number of unique words is 604

For text 1997-Clinton.txt, the number of unique words is 727

For text 2001-Bush.txt, the number of unique words is 593

For text 2005-Bush.txt, the number of unique words is 742

For text 2009-Obama.txt, the number of unique words is 900

Optimize

So we know we can iterate through a list of filenames to analyze individual texts. But just printing the results isn’t very helpful for a scripted analysis! What can we do instead?

We’ll start by making a data frame (a table, essentially) that will hold various attributes about each text. Columns will include “filename”, “year”, “length”, “unique”, etc. That will make it easier to then treat these features like tabular data, so that we can do things like boxplots, t-tests, etc.

import pandas as pd

text_data = pd.DataFrame(columns = ['filename','year','length','unique'])

for file in inaugural.fileids():

word_list = inaugural.words(file)

word_list = [w.lower() for w in word_list] # handle the case sensitivity

this_file = pd.DataFrame(data = {"filename":[file], \

"year" : [int(file[:4])], \

"length" : [len(word_list)], \

"unique" : [len(set(word_list))]})

text_data = text_data.append(this_file, ignore_index=True)text_data| filename | length | unique | year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1789-Washington.txt | 1538 | 604 | 1789 |

| 1 | 1793-Washington.txt | 147 | 95 | 1793 |

| 2 | 1797-Adams.txt | 2585 | 803 | 1797 |

| 3 | 1801-Jefferson.txt | 1935 | 687 | 1801 |

| 4 | 1805-Jefferson.txt | 2384 | 783 | 1805 |

| 5 | 1809-Madison.txt | 1265 | 526 | 1809 |

| 6 | 1813-Madison.txt | 1304 | 524 | 1813 |

| 7 | 1817-Monroe.txt | 3693 | 987 | 1817 |

| 8 | 1821-Monroe.txt | 4909 | 1213 | 1821 |

| 9 | 1825-Adams.txt | 3150 | 972 | 1825 |

| 10 | 1829-Jackson.txt | 1208 | 504 | 1829 |

| 11 | 1833-Jackson.txt | 1267 | 482 | 1833 |

| 12 | 1837-VanBuren.txt | 4171 | 1267 | 1837 |

| 13 | 1841-Harrison.txt | 9165 | 1813 | 1841 |

| 14 | 1845-Polk.txt | 5196 | 1267 | 1845 |

| 15 | 1849-Taylor.txt | 1182 | 488 | 1849 |

| 16 | 1853-Pierce.txt | 3657 | 1124 | 1853 |

| 17 | 1857-Buchanan.txt | 3098 | 902 | 1857 |

| 18 | 1861-Lincoln.txt | 4005 | 1019 | 1861 |

| 19 | 1865-Lincoln.txt | 785 | 345 | 1865 |

| 20 | 1869-Grant.txt | 1239 | 474 | 1869 |

| 21 | 1873-Grant.txt | 1478 | 530 | 1873 |

| 22 | 1877-Hayes.txt | 2724 | 808 | 1877 |

| 23 | 1881-Garfield.txt | 3239 | 981 | 1881 |

| 24 | 1885-Cleveland.txt | 1828 | 650 | 1885 |

| 25 | 1889-Harrison.txt | 4750 | 1313 | 1889 |

| 26 | 1893-Cleveland.txt | 2153 | 799 | 1893 |

| 27 | 1897-McKinley.txt | 4371 | 1199 | 1897 |

| 28 | 1901-McKinley.txt | 2450 | 828 | 1901 |

| 29 | 1905-Roosevelt.txt | 1091 | 388 | 1905 |

| 30 | 1909-Taft.txt | 5846 | 1385 | 1909 |

| 31 | 1913-Wilson.txt | 1905 | 637 | 1913 |

| 32 | 1917-Wilson.txt | 1656 | 529 | 1917 |

| 33 | 1921-Harding.txt | 3756 | 1126 | 1921 |

| 34 | 1925-Coolidge.txt | 4442 | 1164 | 1925 |

| 35 | 1929-Hoover.txt | 3890 | 998 | 1929 |

| 36 | 1933-Roosevelt.txt | 2063 | 715 | 1933 |

| 37 | 1937-Roosevelt.txt | 2019 | 698 | 1937 |

| 38 | 1941-Roosevelt.txt | 1536 | 502 | 1941 |

| 39 | 1945-Roosevelt.txt | 637 | 270 | 1945 |

| 40 | 1949-Truman.txt | 2528 | 745 | 1949 |

| 41 | 1953-Eisenhower.txt | 2775 | 864 | 1953 |

| 42 | 1957-Eisenhower.txt | 1917 | 592 | 1957 |

| 43 | 1961-Kennedy.txt | 1546 | 546 | 1961 |

| 44 | 1965-Johnson.txt | 1715 | 538 | 1965 |

| 45 | 1969-Nixon.txt | 2425 | 714 | 1969 |

| 46 | 1973-Nixon.txt | 2028 | 516 | 1973 |

| 47 | 1977-Carter.txt | 1380 | 504 | 1977 |

| 48 | 1981-Reagan.txt | 2801 | 855 | 1981 |

| 49 | 1985-Reagan.txt | 2946 | 876 | 1985 |

| 50 | 1989-Bush.txt | 2713 | 754 | 1989 |

| 51 | 1993-Clinton.txt | 1855 | 604 | 1993 |

| 52 | 1997-Clinton.txt | 2462 | 727 | 1997 |

| 53 | 2001-Bush.txt | 1825 | 593 | 2001 |

| 54 | 2005-Bush.txt | 2376 | 742 | 2005 |

| 55 | 2009-Obama.txt | 2726 | 900 | 2009 |

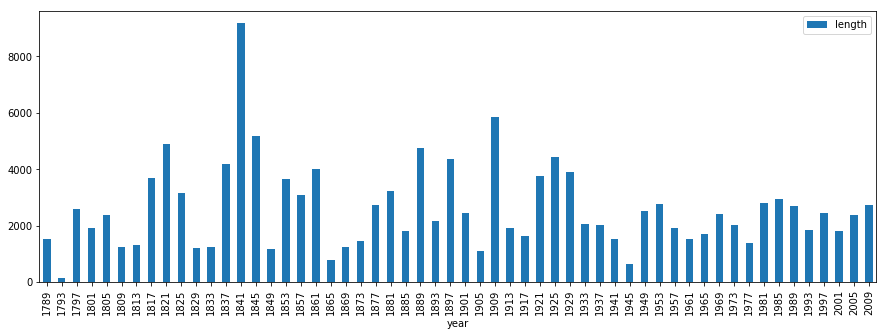

Let’s visualize speech length and number of unique words over our time frame. We’ll start with a simple bar plot of length:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

text_data.plot(kind="bar", x="year", y="length")<matplotlib.axes._subplots.AxesSubplot at 0x118975f28>

That’s too small to read. Let’s try again:

text_data.plot(kind="bar", x="year", y="length", figsize = (15,5)) # 15 cm wide, 5 cm tall<matplotlib.axes._subplots.AxesSubplot at 0x1a219214e0>

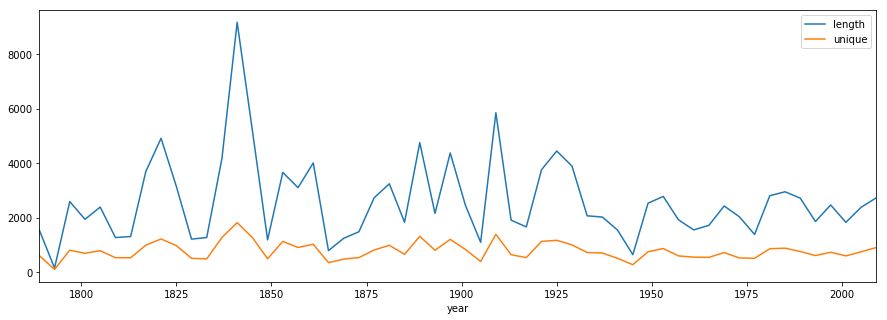

Let’s do both variables in a line plot:

text_data.plot(kind="line", x="year", y=["length", "unique"], figsize = (15,5))<matplotlib.axes._subplots.AxesSubplot at 0x1a21b4bef0>

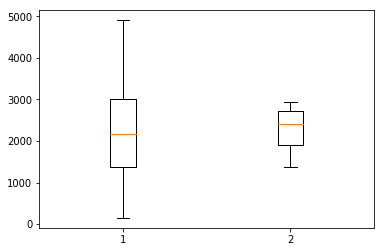

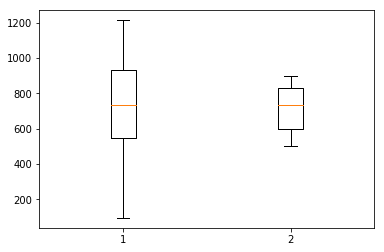

Is there any difference in either the length of speeches or the number of unique words, between the first 10 and last 10 speeches? Let’s look at a boxplot.

early = text_data[:10]

late = text_data[-10:]plt.boxplot([early['length'], late['length']]){'boxes': [<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x1a21edf8d0>,

<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x1a220085c0>],

'caps': [<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x1a22002390>,

<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x1a220027f0>,

<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x1a220142e8>,

<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x1a22014748>],

'fliers': [<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x1a220080f0>,

<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x1a2201a048>],

'means': [],

'medians': [<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x1a22002c50>,

<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x1a22014ba8>],

'whiskers': [<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x1a21edfa20>,

<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x1a21edfef0>,

<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x1a220089e8>,

<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x1a22008e48>]}

Ugh, can we get rid of all that extra verbiage about matplotlib? We can by using plt.show() instead of relying on just the plot itself, which returns lots of info. This time, let’s look at unique words:

plt.boxplot([early['unique'], late['unique']])

plt.show()

Is there a statistical difference, say, in length, between my two timeframes, early and late? We’ll do a two-sample independent T test:

from scipy.stats import ttest_ind

ttest_ind(early['length'], late['length'])Ttest_indResult(statistic=-0.043547585431725419, pvalue=0.9657444852817465)

Unsurprisingly, there is no statistical support to propose that the mean speech length is any different between early and recent inaugural addresses. We can eyeball the same thing in the boxplot for number of unique words. But we do think there are some differences between older and more recent speeches. Maybe the kinds of topics or words? The percentage of all words that are verbs or adjectives? Let’s take a closer look.

A closer look at word frequency

We already took a quick peek at word frequency and we came up with a list that included a lot of obvious words like “the” and “and”. So, how can we get a list of words that actually matter?

We want to get top word frequencies for words that aren’t included in the a list of highly used, unhelpful English words (aka “stopwords”).

from nltk.corpus import stopwords

print(stopwords.words('english'))['i', 'me', 'my', 'myself', 'we', 'our', 'ours', 'ourselves', 'you', "you're", "you've", "you'll", "you'd", 'your', 'yours', 'yourself', 'yourselves', 'he', 'him', 'his', 'himself', 'she', "she's", 'her', 'hers', 'herself', 'it', "it's", 'its', 'itself', 'they', 'them', 'their', 'theirs', 'themselves', 'what', 'which', 'who', 'whom', 'this', 'that', "that'll", 'these', 'those', 'am', 'is', 'are', 'was', 'were', 'be', 'been', 'being', 'have', 'has', 'had', 'having', 'do', 'does', 'did', 'doing', 'a', 'an', 'the', 'and', 'but', 'if', 'or', 'because', 'as', 'until', 'while', 'of', 'at', 'by', 'for', 'with', 'about', 'against', 'between', 'into', 'through', 'during', 'before', 'after', 'above', 'below', 'to', 'from', 'up', 'down', 'in', 'out', 'on', 'off', 'over', 'under', 'again', 'further', 'then', 'once', 'here', 'there', 'when', 'where', 'why', 'how', 'all', 'any', 'both', 'each', 'few', 'more', 'most', 'other', 'some', 'such', 'no', 'nor', 'not', 'only', 'own', 'same', 'so', 'than', 'too', 'very', 's', 't', 'can', 'will', 'just', 'don', "don't", 'should', "should've", 'now', 'd', 'll', 'm', 'o', 're', 've', 'y', 'ain', 'aren', "aren't", 'couldn', "couldn't", 'didn', "didn't", 'doesn', "doesn't", 'hadn', "hadn't", 'hasn', "hasn't", 'haven', "haven't", 'isn', "isn't", 'ma', 'mightn', "mightn't", 'mustn', "mustn't", 'needn', "needn't", 'shan', "shan't", 'shouldn', "shouldn't", 'wasn', "wasn't", 'weren', "weren't", 'won', "won't", 'wouldn', "wouldn't"]

Let’s look at the 15 most frequently used non-stopwords for each inaugural from the early group:

for text in early['filename']:

print (text)

word_list = inaugural.words(text)

word_list = [w.lower() for w in word_list] # handle the case sensitivity

filtered_words = [word for word in word_list if word not in stopwords.words('english')]

print(nltk.FreqDist(filtered_words).most_common(15))1789-Washington.txt

[(',', 70), ('.', 22), ('every', 9), ('government', 8), (';', 8), ('public', 6), ('may', 6), ('citizens', 5), ('present', 5), ('country', 5), ('one', 4), ('ought', 4), ('duty', 4), ('people', 4), ('united', 4)]

1793-Washington.txt

[(',', 5), ('.', 4), ('shall', 3), ('oath', 2), ('fellow', 1), ('citizens', 1), ('called', 1), ('upon', 1), ('voice', 1), ('country', 1), ('execute', 1), ('functions', 1), ('chief', 1), ('magistrate', 1), ('occasion', 1)]

1797-Adams.txt

[(',', 201), ('.', 33), ('people', 20), (';', 18), ('government', 16), ('may', 13), ('nations', 11), ('country', 10), ('nation', 9), ('states', 9), ('foreign', 8), ('constitution', 8), ('honor', 7), ('justice', 6), ('ever', 6)]

1801-Jefferson.txt

[(',', 128), ('.', 37), (';', 23), ('government', 12), ('us', 10), ('may', 8), ('fellow', 7), ('citizens', 7), ('let', 7), ('shall', 6), ('principle', 6), ('would', 6), ('one', 6), ('man', 6), ('safety', 5)]

1805-Jefferson.txt

[(',', 142), ('.', 41), (';', 26), ('public', 14), ('citizens', 10), ('may', 10), ('fellow', 8), ('state', 8), ('us', 7), ('among', 7), ('shall', 7), ('constitution', 6), ('time', 6), ('limits', 5), ('reason', 5)]

1809-Madison.txt

[(',', 47), ('.', 21), (';', 16), ('nations', 6), ('public', 6), ('well', 5), ('country', 4), ('peace', 4), ('rights', 4), ('states', 4), ('confidence', 3), ('full', 3), ('improvements', 3), ('united', 3), ('best', 3)]

1813-Madison.txt

[(',', 53), ('.', 31), ('war', 15), (';', 6), ('country', 5), ('united', 5), ('every', 5), ('british', 5), ('nation', 4), ('without', 4), ('states', 4), ('spirit', 4), ('citizens', 4), ('sense', 3), ('people', 3)]

1817-Monroe.txt

[(',', 169), ('.', 110), ('government', 22), ('great', 21), ('states', 21), ('people', 15), ('us', 14), ('every', 14), ('united', 13), (';', 13), ('may', 10), ('?', 10), ('union', 10), ('war', 10), ('citizens', 9)]

1821-Monroe.txt

[(',', 275), ('.', 130), ('great', 29), ('states', 20), ('would', 18), ('united', 16), ('war', 16), ('citizens', 15), ('may', 15), ('made', 15), ('government', 13), ('every', 13), ('people', 11), ('commerce', 11), ('force', 11)]

1825-Adams.txt

[(',', 115), ('.', 72), (';', 35), ('union', 20), ('government', 17), ('upon', 16), ('country', 10), ('rights', 10), ('peace', 9), ('great', 9), ('public', 9), ('constitution', 8), ('first', 8), ('general', 8), ('nation', 8)]

Hmmm, we still have punctuation in there, which we don’t care about. Let’s remove those, and try again. Note that I’ve added a few random weird punctuation marks that I know will appear later unless I take action now.

custom_stopwords = set((',', '.', ';', '?', '-', '!', '--','"',"'", ':', '¡¦', '¡'))for text in early['filename']:

print (text)

word_list = inaugural.words(text)

word_list = [w.lower() for w in word_list] # handle the case sensitivity

filtered_words = [word for word in word_list if word not in stopwords.words('english') and \

word not in custom_stopwords]

print(nltk.FreqDist(filtered_words).most_common(15))1789-Washington.txt

[('every', 9), ('government', 8), ('public', 6), ('may', 6), ('citizens', 5), ('present', 5), ('country', 5), ('one', 4), ('ought', 4), ('duty', 4), ('people', 4), ('united', 4), ('since', 4), ('fellow', 3), ('could', 3)]

1793-Washington.txt

[('shall', 3), ('oath', 2), ('fellow', 1), ('citizens', 1), ('called', 1), ('upon', 1), ('voice', 1), ('country', 1), ('execute', 1), ('functions', 1), ('chief', 1), ('magistrate', 1), ('occasion', 1), ('proper', 1), ('arrive', 1)]

1797-Adams.txt

[('people', 20), ('government', 16), ('may', 13), ('nations', 11), ('country', 10), ('nation', 9), ('states', 9), ('foreign', 8), ('constitution', 8), ('honor', 7), ('justice', 6), ('ever', 6), ('congress', 6), ('public', 6), ('good', 6)]

1801-Jefferson.txt

[('government', 12), ('us', 10), ('may', 8), ('fellow', 7), ('citizens', 7), ('let', 7), ('shall', 6), ('principle', 6), ('would', 6), ('one', 6), ('man', 6), ('safety', 5), ('good', 5), ('others', 5), ('peace', 5)]

1805-Jefferson.txt

[('public', 14), ('citizens', 10), ('may', 10), ('fellow', 8), ('state', 8), ('us', 7), ('among', 7), ('shall', 7), ('constitution', 6), ('time', 6), ('limits', 5), ('reason', 5), ('false', 5), ('duty', 4), ('every', 4)]

1809-Madison.txt

[('nations', 6), ('public', 6), ('well', 5), ('country', 4), ('peace', 4), ('rights', 4), ('states', 4), ('confidence', 3), ('full', 3), ('improvements', 3), ('united', 3), ('best', 3), ('examples', 2), ('avail', 2), ('made', 2)]

1813-Madison.txt

[('war', 15), ('country', 5), ('united', 5), ('every', 5), ('british', 5), ('nation', 4), ('without', 4), ('states', 4), ('spirit', 4), ('citizens', 4), ('sense', 3), ('people', 3), ('justice', 3), ('part', 3), ('long', 3)]

1817-Monroe.txt

[('government', 22), ('great', 21), ('states', 21), ('people', 15), ('us', 14), ('every', 14), ('united', 13), ('may', 10), ('union', 10), ('war', 10), ('citizens', 9), ('best', 9), ('principles', 9), ('foreign', 9), ('country', 9)]

1821-Monroe.txt

[('great', 29), ('states', 20), ('would', 18), ('united', 16), ('war', 16), ('citizens', 15), ('may', 15), ('made', 15), ('government', 13), ('every', 13), ('people', 11), ('commerce', 11), ('force', 11), ('power', 11), ('fellow', 10)]

1825-Adams.txt

[('union', 20), ('government', 17), ('upon', 16), ('country', 10), ('rights', 10), ('peace', 9), ('great', 9), ('public', 9), ('constitution', 8), ('first', 8), ('general', 8), ('nation', 8), ('people', 7), ('nations', 7), ('duties', 6)]

Better, but again, we want to make the output something that can be the object of computation. Let’s do the following:

- For each of the early and late texts, get their top 15 words.

- Make a list of all of those words

- For each of the “was in a top 15” words, calculate the frequency in each of our texts (early and late)

- Save this info in a data frame

frequent_words = []

for text in list(early['filename']) + list(late['filename']):

word_list = inaugural.words(text)

word_list = [w.lower() for w in word_list] # handle the case sensitivity

filtered_words = [word for word in word_list if word not in stopwords.words('english') and \

word not in custom_stopwords]

top15 = (dict(nltk.FreqDist(filtered_words).most_common(15)).keys())

frequent_words = frequent_words + list(top15)We now have a list of frequent words, but I want to eliminate duplicates (using set()) and alphabetize the list (using sort()).

frequent_words = list(set(frequent_words)) # removes duplicates

frequent_words.sort()

print(frequent_words)['abroad', 'america', 'american', 'americans', 'among', 'arrive', 'avail', 'believe', 'best', 'british', 'called', 'cannot', 'century', 'change', 'chief', 'citizens', 'commerce', 'common', 'confidence', 'congress', 'constitution', 'could', 'country', 'day', 'dream', 'duties', 'duty', 'ever', 'every', 'examples', 'execute', 'false', 'fellow', 'first', 'force', 'foreign', 'free', 'freedom', 'friends', 'full', 'functions', 'general', 'god', 'good', 'government', 'great', 'hand', 'history', 'home', 'honor', 'human', 'improvements', 'justice', 'know', 'land', 'less', 'let', 'liberty', 'limits', 'long', 'made', 'magistrate', 'man', 'many', 'may', 'must', 'nation', 'nations', 'new', 'oath', 'occasion', 'one', 'others', 'ought', 'part', 'peace', 'people', 'power', 'present', 'principle', 'principles', 'promise', 'proper', 'public', 'reason', 'responsibility', 'rights', 'safety', 'say', 'sense', 'shall', 'since', 'spirit', 'state', 'states', 'story', 'strength', 'things', 'time', 'today', 'together', 'union', 'united', 'upon', 'us', 'voice', 'war', 'well', 'without', 'work', 'world', 'would', 'years']

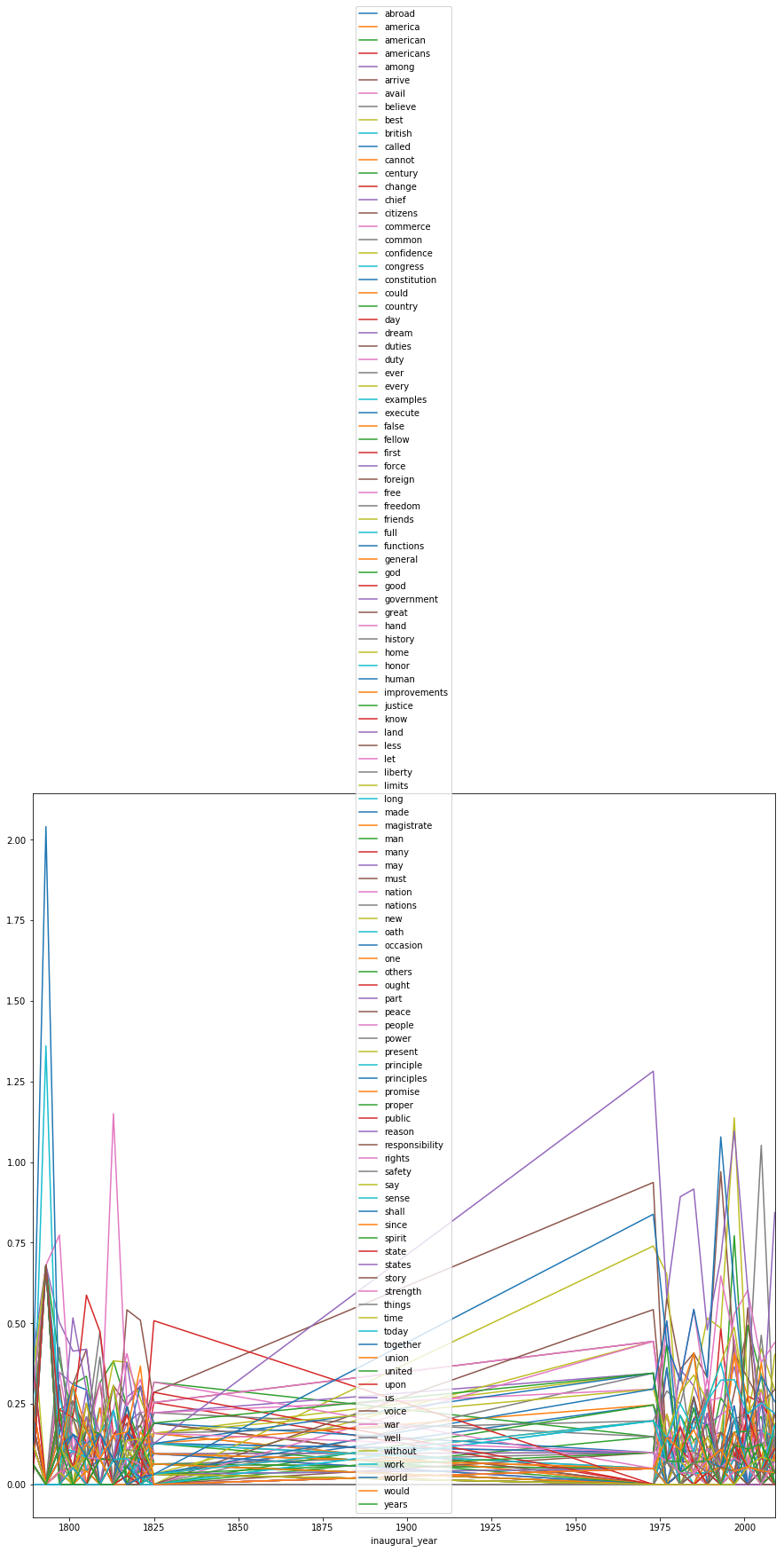

Looks good. Let’s take these words and look at their frequency over time. We’ll transform counts to percent of total words, so as to make an apples-to-apples comparison between speeches of different lengths.

frequency_data = pd.DataFrame(columns = ['inaugural_year','total_length'] + frequent_words)

for text in list(early['filename']) + list(late['filename']):

word_list = inaugural.words(text)

length = len(word_list)

this_freq = {"inaugural_year" : int(text[:4]), "total_length": length}

this_freq.update({word : nltk.FreqDist(word_list)[word]/length*100 for word in frequent_words})

frequency_data = frequency_data.append(pd.DataFrame.from_dict([this_freq]))If I were to look at my data frame now, it would be out of order! Let’s fix that:

frequency_data = frequency_data[['inaugural_year','total_length'] + frequent_words]frequency_data| inaugural_year | total_length | abroad | america | american | americans | among | arrive | avail | believe | ... | upon | us | voice | war | well | without | work | world | would | years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1789 | 1538 | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | ... | 0.000000 | 0.065020 | 0.130039 | 0.000000 | 0.130039 | 0.130039 | 0.000000 | 0.065020 | 0.065020 | 0.065020 |

| 0 | 1793 | 147 | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.000000 | 0.680272 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | ... | 0.680272 | 0.000000 | 0.680272 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 |

| 0 | 1797 | 2585 | 0.038685 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.154739 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | ... | 0.193424 | 0.077369 | 0.038685 | 0.038685 | 0.116054 | 0.116054 | 0.000000 | 0.116054 | 0.077369 | 0.116054 |

| 0 | 1801 | 1935 | 0.051680 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.051680 | 0.000000 | 0.051680 | 0.103359 | ... | 0.051680 | 0.516796 | 0.051680 | 0.051680 | 0.051680 | 0.051680 | 0.051680 | 0.155039 | 0.310078 | 0.000000 |

| 0 | 1805 | 2384 | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.293624 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | ... | 0.000000 | 0.293624 | 0.000000 | 0.083893 | 0.083893 | 0.083893 | 0.000000 | 0.083893 | 0.167785 | 0.083893 |

| 0 | 1809 | 1265 | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.158103 | 0.000000 | ... | 0.158103 | 0.158103 | 0.000000 | 0.079051 | 0.395257 | 0.158103 | 0.000000 | 0.158103 | 0.079051 | 0.000000 |

| 0 | 1813 | 1304 | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.076687 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | ... | 0.000000 | 0.076687 | 0.076687 | 1.150307 | 0.000000 | 0.306748 | 0.076687 | 0.076687 | 0.153374 | 0.000000 |

| 0 | 1817 | 3693 | 0.027078 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.081235 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | ... | 0.027078 | 0.379096 | 0.000000 | 0.243704 | 0.108313 | 0.081235 | 0.081235 | 0.000000 | 0.162470 | 0.054157 |

| 0 | 1821 | 4909 | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.020371 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.020371 | ... | 0.000000 | 0.122224 | 0.000000 | 0.325932 | 0.101854 | 0.142595 | 0.000000 | 0.020371 | 0.366673 | 0.122224 |

| 0 | 1825 | 3150 | 0.031746 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.095238 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | ... | 0.507937 | 0.126984 | 0.031746 | 0.158730 | 0.000000 | 0.031746 | 0.031746 | 0.031746 | 0.000000 | 0.190476 |

| 0 | 1973 | 2028 | 0.246548 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.049310 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | ... | 0.000000 | 1.282051 | 0.000000 | 0.098619 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.197239 | 0.838264 | 0.049310 | 0.345168 |

| 0 | 1977 | 1380 | 0.072464 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.144928 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.072464 | ... | 0.072464 | 0.579710 | 0.000000 | 0.072464 | 0.072464 | 0.000000 | 0.144928 | 0.434783 | 0.144928 | 0.072464 |

| 0 | 1981 | 2801 | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.142806 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.357015 | ... | 0.178508 | 0.892538 | 0.000000 | 0.035702 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.249911 | 0.321314 | 0.107105 | 0.071403 |

| 0 | 1985 | 2946 | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.067889 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.067889 | ... | 0.067889 | 0.916497 | 0.000000 | 0.033944 | 0.067889 | 0.000000 | 0.169722 | 0.543109 | 0.169722 | 0.237610 |

| 0 | 1989 | 2713 | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | ... | 0.000000 | 0.479174 | 0.000000 | 0.073719 | 0.036860 | 0.000000 | 0.258017 | 0.331736 | 0.073719 | 0.073719 |

| 0 | 1993 | 1855 | 0.053908 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.053908 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | ... | 0.000000 | 0.700809 | 0.053908 | 0.000000 | 0.107817 | 0.000000 | 0.323450 | 1.078167 | 0.107817 | 0.000000 |

| 0 | 1997 | 2462 | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | ... | 0.121852 | 1.096669 | 0.040617 | 0.040617 | 0.040617 | 0.000000 | 0.324939 | 0.609261 | 0.040617 | 0.121852 |

| 0 | 2001 | 1825 | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.109589 | ... | 0.054795 | 0.602740 | 0.000000 | 0.054795 | 0.054795 | 0.054795 | 0.219178 | 0.164384 | 0.054795 | 0.109589 |

| 0 | 2005 | 2376 | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.042088 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.084175 | ... | 0.042088 | 0.126263 | 0.042088 | 0.000000 | 0.042088 | 0.084175 | 0.252525 | 0.336700 | 0.042088 | 0.126263 |

| 0 | 2009 | 2726 | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.036684 | ... | 0.110051 | 0.843727 | 0.000000 | 0.073368 | 0.073368 | 0.073368 | 0.220103 | 0.256787 | 0.036684 | 0.036684 |

20 rows × 115 columns

We know we have over 100 frequent words! What if we dared to do a line plot? Should we?

frequency_data.plot(kind="line", x="inaugural_year", y=frequent_words, figsize = (15,15))<matplotlib.axes._subplots.AxesSubplot at 0x11654cfd0>

Ugh, no. Keep in mind a couple of things here:

- We’re dealing just with the first and last 10 speeches

- We want to identify some words that might have changed over the years in their frequency.

So we’ll get early averages and late averages, subtract them, and see where the biggest differences lie.

early_means = frequency_data[:10].agg(['mean'])

late_means = frequency_data[-10:].agg(['mean'])Take the absolute value of the differences, which will give us a one-row data frame. Transpose that (so it becomes one column) and “squeeze” it into a series (a vector of values). The sort it from highest to lowest.

abs(early_means-late_means).T.squeeze().sort_values(ascending=False) inaugural_year 184.000000

total_length 20.200000

us 0.570428

new 0.446940

world 0.420759

must 0.337502

shall 0.271204

may 0.260966

freedom 0.244255

public 0.219485

work 0.211866

time 0.201468

today 0.170451

country 0.169244

nation 0.169082

war 0.164875

together 0.139093

confidence 0.135190

history 0.131981

present 0.129296

century 0.127500

citizens 0.125357

know 0.117670

honor 0.114258

one 0.113810

let 0.112489

promise 0.109395

day 0.106852

foreign 0.106448

functions 0.100854

...

first 0.025484

long 0.025180

ever 0.023124

spirit 0.023065

abroad 0.022373

common 0.021743

many 0.021489

safety 0.021131

avail 0.020978

peace 0.020686

every 0.019590

union 0.018192

congress 0.016173

others 0.014613

constitution 0.011238

part 0.011056

chief 0.010377

good 0.010333

great 0.010064

false 0.008705

less 0.005906

best 0.002286

power 0.001589

british 0.000000

states 0.000000

americans 0.000000

american 0.000000

america 0.000000

god 0.000000

magistrate 0.000000

Name: mean, Length: 115, dtype: float64

The first two values, inaugural_year and total_length, don’t really matter – means on those values don’t matter for us. But we see fairly large differences in the use of “us” (probably confounded with “US”?), new, world, must, shall, may, freedom, public, work, and time.

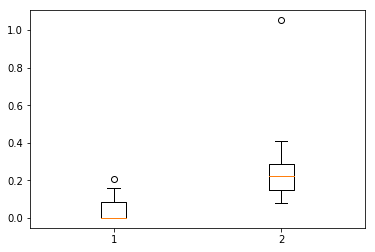

Let’s take a look at the difference in the use of the word “freedom”:

early_freedom = frequency_data[:10]['freedom'].squeeze()

late_freedom = frequency_data[-10:]['freedom'].squeeze()

plt.boxplot([early_freedom, late_freedom])

plt.show()

Wow, there’s much higher use of the word “freedom” in later texts. Is the difference significant?

ttest_ind(early_freedom, late_freedom) Ttest_indResult(statistic=-2.6395050293418394, pvalue=0.016653997891435467)

Yep, it looks like the difference in the word “freedom” is statistically significant in these speeches. This could indicate a number of things, like the frequency of the word in general spoken English (perhaps “liberty” or another word was preferred in the early years of the United States?), political changes, or thematic differences in the speeches.

In subsequent NLP-related posts, we’ll talk about how to do part-of-speech tagging and other metrics that can help analyze texts. Stay tuned!